Visible Neurodivergent Executive Leadership: A Missing Piece in Neuroinclusive Cultures

Laura Kendall

6/10/2025

Where Are All the Neurodivergent Senior Execs?

One of the richest privileges of launching NeuroFuel has been connecting with senior leaders across different sectors; health, education, professional services, tech, government, and more. Time and again, I’ve been asked: “Who’s a neurodivergent executive I might know?”

That question always gives me pause. Not because such leaders don’t exist (we do!) But because if I set aside founders and business owners, the number of openly neurodivergent serving executives is astonishingly small. I can still count the ones I personally know on one hand, and have fingers left over.

Statistically, this makes little sense. Current data suggest that at least 1 in 7, and possibly as many as 1 in 5 people (around 20 per cent) may be neurodivergent. Yet in workplaces, many professionals choose not to disclose. In a 2023 poll by the Institution of Occupational Health and Safety, 72 per cent of neurodivergent individuals reported that they had not told their employer about their neurodivergence. From my own conversations, my impression is the non-disclosure rate is even higher among those in leadership roles, likely shaped by reputational risk, exposure, and structural pressures. (A.k.a. discrimination.)

It reminds me of another context. Not a single player in the AFL men’s competition has ever come out publicly as gay or bisexual during their playing career. In a league of many hundreds, the absence of openly gay players is more about safety and stigma than numbers. The situation with openly neurodivergent executives in Australian businesses is strikingly similar.

Why Visibility Matters

1. Psychological safety and belonging

For neurodivergent employees, especially early in their careers, seeing someone more senior who shares aspects of their neurotype can feel like permission to be themselves. It communicates: “You belong. You don’t have to hide.” Many tell me that knowing openly neurodivergent executives exist gives them strength, confidence to disclose (if they want), and increases their commitment to stay and thrive.

2. Signalling real inclusion, not just intentions

Policies, training, and pronouncements are necessary but not sufficient. When senior neurodivergent leadership remains invisible or silent, it sends a tacit message: “It’s not safe to show up fully here.” Visible leaders can help shift norms, open dialogue, reduce stigma, and model how vulnerability and authenticity can coexist with effectiveness.

3. Unlocking organisational value

Inclusive, neurodiverse teams deliver strong business outcomes. Evidence shows that organisations leading on inclusion generate about 25 per cent more revenue per employee than their industry peers (Accenture, 2023). Studies show gains in innovation, productivity, error reduction, and resilience when neurodiversity inclusion is done well. For example, in EY’s latest Neuroinclusion at Work study, respondents who felt “truly included” reported up to 34% higher proficiency across in-demand skills (AI, resilience, leadership) compared to those who did not feel included.

Visible neurodiverse leadership is not just aspirational. It is a lever for unlocking latent organisational capacity.

Barriers to Visibility and Disclosure

Fear of stigma or career penalty. Research consistently shows neurodivergent professionals are concerned disclosure would be perceived as exposing “weakness,” and risk bias in promotion, assignment, or peer perception.

Lack of culture or precedent. If no one senior shows up as neurodivergent, the default is concealment.

Misunderstanding about what “disclosure” means. It need not involve medical documentation or making a public statement. It can be a conversation about needs, preferences, or identity in safe contexts such as internal forums or employee resource groups.

Structural risk and legal caution. Some leaders may feel hemmed in by discrimination from multiple directions (e.g. board expectations, investor optics, regulatory exposure), making open disclosure risky.

Over-emphasis on “accommodations” over systemic change. Many neuroinclusion efforts remain focused on individual adjustments rather than shifting culture, norms, and systems.

These barriers don’t justify silence. They underscore why visible leadership is so needed.

Questions for Neurotypical Leaders

If senior neurodivergent leaders aren’t disclosing, do you have reason to believe your culture is truly safe for them to do so?

Are you comfortable stating that your organisation genuinely meets its psychological safety, WHS (work health and safety), and fiduciary obligations, especially in the domain of neuroinclusion?

What would it take for your leadership team to model authenticity in this space, not just talk about inclusion, but live it?

You don’t need neurodivergent leaders to be forced into disclosure, but you do need cultures that make disclosure a safe option, not a risk.

How Organisations Can Support Greater Visibility (When Individuals Are Ready)

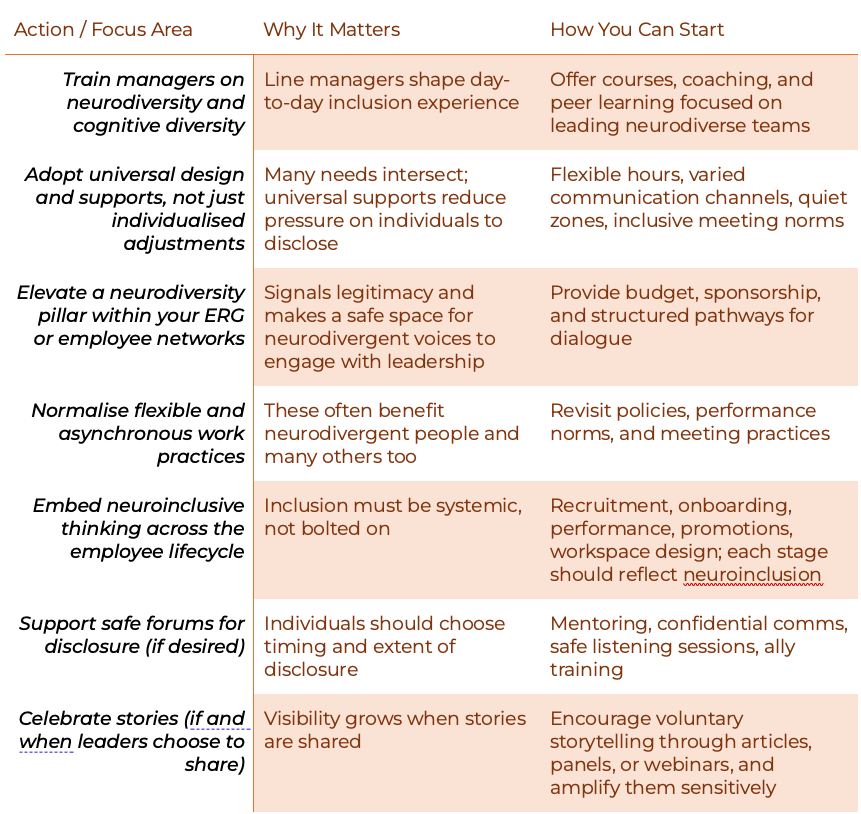

Here are practical levers to help move beyond performative inclusion toward real change:

Ready to Lead the Change?

I want to emphasise: I’m not advocating that any neurodivergent leader be forced or pressured to “come out.” That decision is deeply personal, situational, and complex. The goal is to create cultures in which revealing one’s neurotype is safe, not brave.

If neurotypical leaders are serious about inclusion, you must ask: are we doing enough to make disclosure optional rather than too risky to contemplate?

I’d love to hear from you:

If you are (or know) an executive leader who has navigated disclosure, what helped you feel safe?

If you are a non-neurodivergent leader, what’s the hardest part of stepping into vulnerability in this space?

What one action could your organisation take before the end of 2025 to move toward greater psychological safety for its neurodivergent people?

Let’s make inclusion real, visible, and human, not just aspirational.